In France, the prevalence of NAFLD is about 25 % among adults, of which 16% are estimated to have NASH. Mathematic modelisation have estimated that the prevalence of severe liver disease due to NAFLD would be increased by 2 of in the next 15 years1, 2.

NAFLD, characterized by excessive accumulation of fat in liver tissue (≥5 % of hepatocytes), includes two distinct liver diseases:

- Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, limited to simple steatosis,

- And Non-Alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Since excessive consumption of alcohol is a frequent etiology of fatty liver disease, NAFLD is diagnosed if the daily alcohol consumption is < 20 and 30 g/d in women and men, respectively. It is associated with metabolic syndrome and/or or insulin resistance1.

The definition of NASH associates three histological abnormalities: steatosis, ballooning of hepatocytes and lobular inflammation.

Steatosis, or fatty liver, leads to NASH in 20 % of patients and, in this case, to fibrosis injuries in 30 % of them. Cirrhosis occurs in 20 % of patients with fibrosis injuries and complications of cirrhosis in about 20 %, as in other etiologies3, 4.

Identified risk factors of severe liver disease are the following: metabolic syndrom, increased ALAT, ASAT, of alkalines phosphatase, insulin resistance, and overweight for the evolution to NASH; initial value and the evolution of ASAT, ALAT, and NAS score, histological injuries (steatosis, necro-inflammatory injuries, and fibrosis) for the fibrosis.

Since NAFLD is a frequent and asymptomatic disease before the occurrence of a decompensation of cirrhosis, a systematic screening is indicated in all patients with one of the metabolic risk factors, with an ultrasound exam and a dosage of liver enzymes.

The screening with ultrasound exam has to be performed systematically, even in absence of elevated ALAT and ASAT, since they can be normal or fluctuating. The evaluation of fibrosis is necessary in all patients, but particularly in those with risk factors of fibrosis (age higher than 50, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrom) because of its prognosis implications2, 3, 5.

Subjects with NAFLD should be screened for secondary causes of accumulation of liver fat, including cofactors of fibrosis (as alcohol consumption), eliminate concurrent diseases (drug-induced fatty liver disease, chronic hepatitis C related to genotype 3 infection…) and all coexisting liver diseases which might result in more severe liver injuries5.

The interaction between low alcohol consumption and metabolic factors should be considered. The lifestyle of the patient has to been evaluated, such as food and activity habits. At least, since the first cause of mortality in patients with NAFLD is cardiovascular, the screening of cardiovascular diseases is mandatory in all patients, after a detailed risk factor evaluation6.

Concerning the liver disease itself, there are three aims in patients with a suspected NAFLD:

- To confirm or not the diagnosis of NAFLD,

- To screen the NASH (because of its association with the risk of fibrosis),

- To screen severe liver fibrosis (cirrhosis or pre-cirrhosis) indicating the systematic screening of cirrhosis complications (including the hepatocellular carcinoma and portal hypertension). 2,3,5

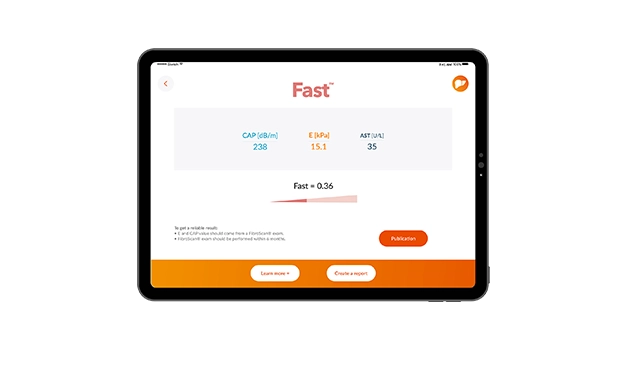

If the criteria of definition of NAFLD and NASH are histological and need a liver biopsy, the non-invasive tests are useful to avoid the morbidity and the mortality related to this exam7, 8. For diagnosis of steatosis, the best quantitative estimation of liver fat is performed by 1H-MRS but since this exam is expensive, the ultrasound exam is still the ideal first-line diagnostic procedure; serum biomarkers and scores being recognized by recent international guidelines as acceptable alternatives5, 9.

For the diagnosis of fibrosis injuries, biomarkers, scores, and transient elastography are considered as acceptable: the combination of both could increase diagnosis accuracy and then decrease the number liver biopsies7.

The evaluation of liver disease during the follow-up of patients are usually performed with biomarkers and transient elastography (international guidelines of 2016, for a validation with non-invasive tests).

In conclusion, early diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis is necessary in all patients with metabolic abnormalities because of their high and increasing prevalence in the general population, the high risk of severe fibrosis injuries (including cirrhosis and its complications) and the efficacy of the management of the components of the metabolic syndrome10, particularly at an early stage of the liver disease.

If the pharmacotherapy is currently reserved for a minority of patients characterized by a severe NASH, promising novel agents with anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic or insulin sensitizing properties are in development, with the hope to control this endemic liver disease in Western countries and probably in the future, in others countries.

References :

- 1. Dyson J, Jacques B, Chattopadyhav D, Lochan R, Graham J, Das D et al. Hepatocellular cancer: the impact of obesity, type 2 diabetes and a multidisciplinary team. J Hepatol 2014; 60(1):110-

- 2. Younossi ZM, Koening AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analysis assessment of prevalence, incidence and outcomes. Hepatology 2016; 1(64):73-84.

- 3. Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Aug;34(3):274-85.

- 4. Traussnigg S, Kienbacher C, Halilbasic E, Rechling C, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Hofer H, et al. Challenges and Management of Liver Cirrhosis: Practical Issues in the Therapy of Patients with Cirrhosis due to NAFLD and NASH. Dig Dis. 2015; 33(4):598-607.

- 5. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). J Hepatol 2016 Jun; 64(6):1388-402.

- 6. Lonardo A, Sookoian S, Pirola CJ, Targher G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of cardiovascular disease. Metabolism 2016; 65 (8):1136-50.

- 7. Boursier J, Vergniol J, Guillet A, Hiriart JB, Lannes A, Le Bail B, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and prognostic significance of blood fibrosis tests and liver stiffness measurement by FibroScan in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016 Sep; 65(3):570-8.

- 8. Van Katwyk S, Coyle D, Cooper C, Pussegoda K, Cameron C, Skidmore B, et al. Transient elastography for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Liver Int. 2017; 37(6):851-861.

- 9. Sanyal AJ, Friedman SL, McCullough AJ, Dimick-Santos L. Challenges and Opportunities in Drug and Biomarker Development for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Findings and Recommendations from an American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases–U.S. Food and Drug Administration Joint Workshop. Hepatology 2015; 61:1392-1405.

- 10. Kenneally S, Sier JH, Moore JB. Efficacy of dietary and physical activity intervention in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000139.

article initialy written in 12.2017